Impossible Things

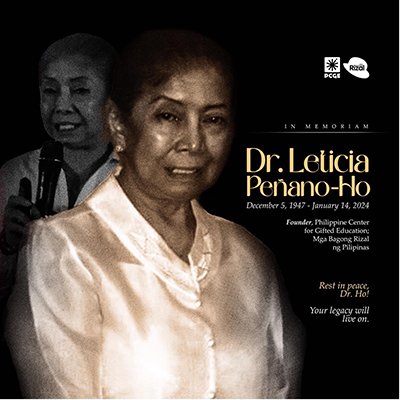

(Courtesy of the Philippine Center for Gifted Education and the Mga Bagong Rizal program)

Dr. Ho saying no. Dr. Ho running out of questions. Not knowing the right things to say. Dr. Ho idle. Dr. Ho not asking me about what I am “currently working on.” Dr. Ho ceasing to be the burst of energy that she is.

I spent many evenings with Dr. Ho—mostly in her office at the University of the Philippines in Diliman, a few, in Baguio for her advocacy work, some in shared hotel rooms where we gossiped with her staff, the printer whirring in the background as we rushed some form of paperwork. But these evenings when we were having fun at work were not what I instantly remembered about her when I heard the news. It was when I found out she was a literature major herself.

“Yes,” she confirmed. “I studied literature, and I could not express myself in Tagalog very well as a child, so my mother brought me Liwayway to read.”

I was 20. I was in my final year at university, and I was in Quezon City to volunteer for a convention by the Philippine Center for Gifted Education (PCGE), the organization dedicated to gathering and supporting gifted persons in the country.

We were at a Pancake House, some of its branches the venues the setting of my memories with Dr. Ho. We both ordered fish rolls and Coke, and it thrilled me that not only were we connected by field, but now by food choice.

Emboldened by the feeling that we were kindred souls, I told her that I was looking for an organization where I could intern. “Something that is equal parts development work and academic work” was what I told her. Come to PCGE, she said. She asked me to keep in touch with her longtime assistant, Mygee del Rey, who became one of my closest friends. That was the evening Dr. Ho took me under her wing.

The first floor of Benitez Hall, home of the College of Education at UP Diliman was where PCGE was based. It was where most of my favorite memories of Dr. Ho and her team happened.

They billeted me at Yakal, one of the 12 residence halls at UP, a short ten-minute walk to the office, which might as well be ten kilometers as I usually got lost in the maze leading to UP Oval. And because it was the height of summer, I would show up barely on time, drenched in sweat and stress, while everyone was fresh and cheery.

We would work through the day, filing documents, writing copy, and sending out e-mails for conventions, seminars, and workshops the center was organizing. Dr. Ho would come in by the late afternoon, sometimes staying until 10 p.m., and these were moments I always look forward to.

Speaking was her strength, and I was all ears. We talked about her research and studies. She was a student of Howard Gardner who developed the Theory of Multiple Intelligences. We talked about writing proposals and pitching them. We discussed books we adored.

When she did not want to respond to a question, she would subtly throw more questions back at you. By the time you found yourself saying more about yourself than actually hearing her responses, it would be too late.

Dr. Ho served two terms as the Dean of the College of Education before focusing on her advocacy work and teaching at the graduate school. She was the founder of the PCGE, and the President of the Philippine Association for the Gifted. I met her at the Mga Bagong Rizal Awards, PCGE’s flagship program that searches for 35 “gifted young people around the Philippines” for a series of leadership workshops in Manila. I was nominated in 2011 for linguistic intelligence and was part of their first batch. Dr. Ho used her former teacher Dr. Gardner’s theory as a program framework.

“Have you seen the bright kids in the infant formula commercials?” an emcee once asked in introducing Dr. Ho. “Those are kids this lady mentored.”

Her idea of “giftedness” was scientific, but also personal. “This is why I worked with her for as long as I did,” Mygee told me the night we heard the news. “That kind of advocacy is not popular in the Philippines, and she made it her own.”

Dr. Ho implemented tests, ran brain scans, and conducted brain mapping. Organizations and corporations consulted with her, and she provided counseling services. But Dr. Ho also understood giftedness amid Philippine reality. Many gifted Filipinos’ potentials were wasted because they were not recognized, she once told me. They could not afford the education, tests, the reinforcements. This inspired her to build PCGE.

“There is a Fernando Amorsolo or Vicente Manansala somewhere waiting to be discovered, but their parents can barely afford food, so how can they buy watercolor?”

The Rizal program was among the few I joined in college that kept up with its alumni longitudinally. Some of the students in my batch were supported by PCGE in generous ways. Backed by sponsors, PCGE gave every awardee a laptop at the end of the program. Some were given financial aid to defray education costs. Dr. Ho wrote recommendation letters for us as we forayed into the workforce. They sponsored a mentoring session for me with the late National Artist for Literature, F. Sionil Jose, a writer I had read as a younger student.

The author (rightmost) and Dr. Ho (third from right) with F. Sionil Jose after a session at the Bahay ng Alumni, UP Diliman.

In the years following the Rizal Awards and my internship, she would casually slide into my Inbox and inquire about what project I was working on.

“Are you writing a book?” she would ask.

“No, ho” was one of my replies to this constant inquiry, followed by a grinning emoji. I teased her by disguising her married name as a polite marker. It was one of my attempts to get her to laugh. It worked.

For all that she had done, Dr. Ho never appeared as a mother figure to me. I don’t think she ever was to anyone else she mentored. She was close to us, but always at an arm’s length. She never doted. One profile dubbed her as the “godmother of the Philippine gifted.” I wonder if she had seen that moniker and cringed. She wasn’t impressed by anything wishy-washy. She had to see something: “Show me your progress, name your project. Give me the data.” Until the very end, she expected nothing but the best.

I kept to myself in my twenties. The pressure of work and disillusionment with former teachers and the academe took its toll and I stopped writing altogether. Dr. Ho would appear in my Inbox now and then, asking me to come to Manila to help facilitate her workshops, speak at a sponsor’s event, emcee for PCGE’s convention, all expenses reimbursable.

The author and Dr. Ho. Following a spoken word performance by the author at the 2014 Convention of the Philippine Association for the Gifted, Quezon City.

And each time, I made excuses.

I had essays to grade. I was overseas. I’d be at another event that day, sorry.

It was the pandemic that made me realize what she was always been offering me: opportunity. She knew her students were capable, and we would eventually figure things out in our own ways. Yet, as any good mentor would do, she made sure doors were open for someone like me, when I was ready to enter.

It was a little late when I did. She wrote an assessment of my work and a recommendation letter for a research fellowship I applied for at a university in Singapore when the pandemic started. The program migrated online due to travel restrictions. She called to check on me.

“I’m fine,” I lied. I was exhausted. Interviews had been done, data packaged, and I was excited to meet my adviser and write the study abroad.

“But I’m not,” Dr. Ho said. And then something rare happened. She told me about her frustrations, her inability, fear, and anxiety. She was not able to work, could not reach her usual productivity. I imagined how, for the first time in a long while, that scared her, too.

“This will not go on forever,” she said. “Let’s try again.”

We searched for another door, and she wrote me another recommendation letter.

***

The news came in January 2024. It was winter where I was. Cold, brutal. That was a long month.

Mygee sent me the message, and I read it right before going to bed.

During the lockdowns, we said a short prayer together over the phone. In a way, it was our goodbye. It did not make things feel easy but somehow real. No one would slide into my DMs anymore. No one to talk to about my research or scholarship evaluators.

“Dr. Ho also understood giftedness amid Philippine reality. Many gifted Filipinos’ potentials were wasted because they were not recognized, she once told me.”

She did write a recommendation letter for me, the last one as it now turned out, to an exchange teaching program in Japan. “Use the time to be away and to rest,” she instructed me. “Think of it as a paid vacation.”

I was watching a clip of Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland, in their office shortly before my internship in 2011, at when she chanced upon my screen.

“I do not care much about the movie, but the book was one of my favorites,” she said.

“It’s a little dark, but it’s fantastic,” I convinced her. “Wicked Tim Burton. I like the part where she can think of six impossible things before breakfast.”

“One: I will get rich,” she teased.

“Two: I’ll write a book,” I said. She had been nudging me to compile my essays for a book.

“You have to write one someday,” she retorted.

“Maybe I’ll write about you,” I grinned.

She peered at me through her gold-rimmed glasses.

“You will not find anything about me worth writing. So that’s another impossible thing.”

Not quite, ho, Doc. For now, rest easy.

Ian Layugan hails from Baguio City and is currently based in Gunma Prefecture, Japan where he works with the Kiryu City Board of Education under the Japan Exchange and Teaching Programme. He has written for Rappler and has led research projects for Oxfam, Asmae International, and the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore. Follow him on Instagram/Twitter at @ianlayuganx.

More articles from Ian Layugan

No comments:

Post a Comment