Portrait of the Filipino as a Book Designer

Felix Magi Miguel and Criselda Yabes (Photo courtesy of Criselda Yabes)

I arrived in time to pick a dessert from the expensive menu. A single slice of a carrot cake lasted throughout the afternoon of conversing with Felix about anything that popped on our minds. It was as if we were continuing our conversation from the last one several months ago, when he had his first solo painting exhibition in Manila as the lockdown was loosening up.

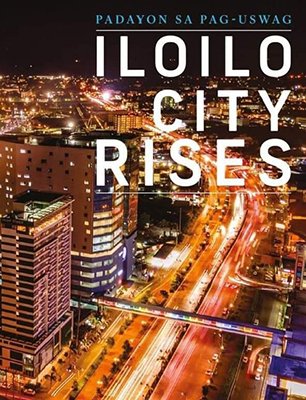

The Iloilo coffee table book is set to make a stamp on the revival of the city’s grandeur, from its colonial past to the present. I relished the idea that I was meeting Felix here. The book is going to be the 150th+ he has designed throughout his career, which zoomed right off when he finished his degree in Fine Arts at the University of the Philippines in Diliman in the early 1990s.

“Iloilo Rises”

There are so many quotable quotes from our conversations; some shocking, some personal and political; but usually boiled down to the passion of creating. Does it make his work less Filipino because he uses western font and style? (Me: is there no end to this inconsequential debate?)

Felix says his designs are patently Filipino “because I’m a Filipino. I breathe it out.” To him it’s as simple as “I create them because I love beautiful creations.” His work of art is his own identity.

In fact, about a month after our talk over carrot cake, he was in Manila for the opening of an exhibit by The Design Center of the Philippines at the National Museum of Fine Arts, honoring Philippine-made designs mostly of indigenous materials, like chairs, for example, for the last 50 years. And for the first time it brought out book designs, acknowledging Felix’s reputation of putting his skills into an art form. Later, in February, Felix received Metrobank Foundation’s prestigious Award for Continuing Excellence and Service, or ACES, that comes every five years. Previous to that, he received second place in Metrobank’s Art and Design Excellence in 1989.

In our next conversation at my preferred café near the university campus, we carried on into the theme of love. Not romantic love, but the love for oneself when creating a piece that would extend that sentiment to anyone who would make use of the piece. We were talking spiritually now, or was it metaphysically? If, for example, he makes a chair, the person that will be sitting on it will feel the love, because it was created out of love for oneself and others.

To which, I said, I was more interested in finding true love, with an entourage of nurturers seeing you through the stages of creation. Felix has been blessed with that. The support from his family in pursuing his talent opened a door that led to others welcoming his métier. He went to high school at the famous art school in Mount Makiling in Laguna. He wanted to be a painter (he was also into music), which took him to the campus in Diliman where he would meet his future wife and the mentors that guided him.

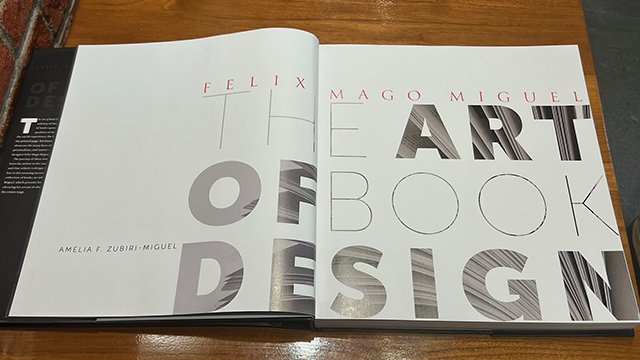

His first jobs were for children’s books, gradually spreading out into art and history books – broadening the scope of his work, allowing any reader to sigh in the awe of his design and layout. Felix was breaking from the standard coffee table books that you leave on the shelf for dust to gather. His was made for keeps. His wife of 25 years, Amel, a writer and editor herself, has put together the essential trademark of Felix Mago Miguel in the book The Art of Book Design (published in 2022 by the Foreign Service Institute).

Miguel’s “The Art of Book Design”

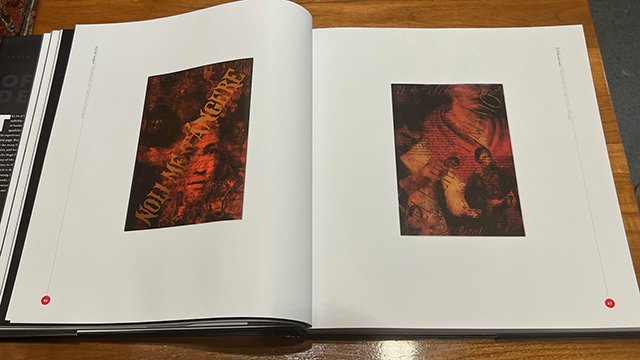

Miguel’s design for “Noli Me Tangere”

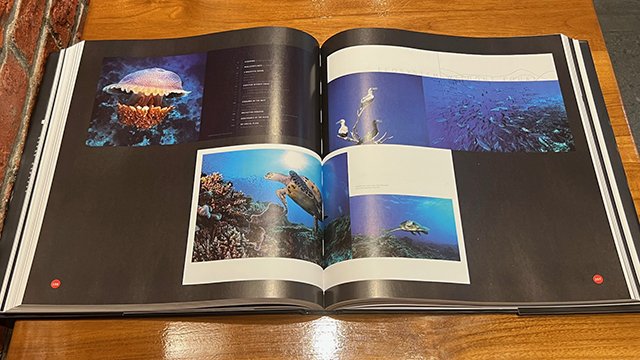

Miguel’s design for “Tubbataha: Art of Nature”

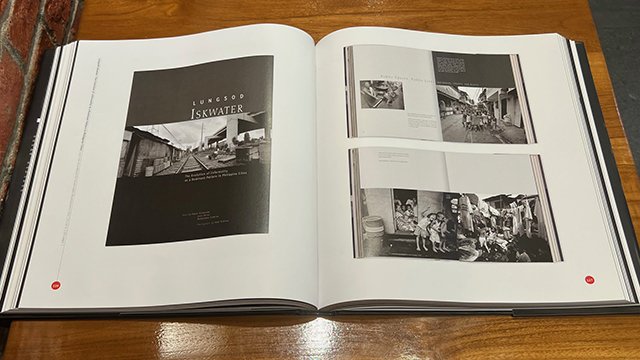

Miguel’s design for “Lungsod Iskwater”

In 264 pages, you will just about see the breadth of Felix’s devotion to making the subject of a book speak for itself, in either black-and-white or color. You will also know his story -- the boy who grew up in Sta. Ana , Manila, near the San Juan River that usually threatened to flood their family home during monsoons, and the image that he recounts of rushing to the upper floor of the house with all the furniture . It tells us so much more of where he came from and why we, in our conversations, can peel out bit by bit the sad ethos of our country’s divisions and aspirations.

When they were starting a family, Felix and Amel had fraternal twins and named the boy Ulan (Rain) and the girl, Ulap (Cloud). They bore three more children in fairly quick succession: Araw (Sun), Angin (Wind), and finally, Langit (Sky). Altogether, the Miguels stuck to the core of nature and original language. Their move to Bohol island in 2005 – away from the big city where Amel was running a tutoring center and library for children – brought them closer to the elements of an island lifestyle. The children themselves have acquired the Miguel DNA, being artists in their own right.

It was in Bohol where I met Felix, through my sister with whom he worked for book projects by the Ateneo de Manila University. I’d see him again in Bohol a few years later, inadvertently starting the beginning of our on-again, off-again series of conversations. By then, he and Amel had become devout Christians.

But it was really the birds that got us rolling. During the pandemic, when he was turning 50, the diminishing hours of duty and work gave him room to paint as he had always wanted. His canvases resulted in a magnificent collection of the half-woman, half-bird image for a show he called Album: Filipinas at the Altro Mondo gallery in Makati. Almost all the paintings were sold out, most of them ostensibly bought by a single collector.

It had women in their finest colonial dresses, their heads replaced by symbolic objects depicting the old Spanish history of our times. What I loved most were the varied species of the sunbirds. All of them had undertones of the lives of Filipinas subjected to their fates when the friars were around. These were not the Maria Claras; these were the women Felix unearthed from his research on the web for more pictures and history.

At least, he gave voices to the Filipina through the birds with curved, pointy beaks, like the downturned moustache of Salvador Dali. In the gallery’s year-end show, there was my spark bird, the kingfisher whom Felix named Filomena Kahirup (which means “love together” or “together, love,” but which also hearkened back to the ironies of the elite Kahirup Ball with an offering of a lowly dried danggit, a fish commonly caught and eaten in the Visayas).

This, I think, was where we began exchanging our knowledge, views, and pain about the outcome of becoming a Filipino. At some point, I had stopped taking notes and veered inwards, as Felix’s voice expressed not only his love for art, but also the tragic disappointments we shared about our country. As for the birds in his painting, they spoke freely within the frame of his canvas.

Then it occurred to us that we had never worked together on a book – me writing, he designing. We want to make it happen, but we don’t know when. In the meantime, he has done his second collection of the women-birds, also exhibited at the Altro Mondo, and this time on the theme of the American colonial presence. He was serious about going through the Philippine saga, lining up his future collection on the Peacetime era, through the Second World War, past our Independence, and perhaps right up to the Anti-Drug War.

Felix says his designs are patently Filipino “because I’m a Filipino. I breathe it out.”

I missed the last day of his exhibit, the day after I arrived jetlagged from France. There was no other way but to meet in Iloilo the following week, where by chance I would be part of a writers’ workshop while he was winding up the Iloilo coffee table book project. We had more than three hours to spare before his flight out.

I was excited to tell him about the Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas exhibit at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris last summer. I was rambling on about Le Repos – how it could fit into a Filipina. Felix pulled out his phone and scrolled his gallery, finding the photo he wanted to show me instead. It was his version of Manet’s Olympia, derived from an image of a nude indigenous Filipina taken by an American explorer. He had seen the photo on an online library and couldn’t get his mind off it. Around her were birds, the little birds I could identify from my field guide.

One day, I promised myself from that moment, a Felix Mago Miguel work of art will be on my living room wall. In God’s time, I heard him say. I said the same thing to myself.

Criselda Yabes is a writer and journalist who has written about a dozen books, some of them on the military and Mindanao.

She now lives in northeast France and comes home to the Philippines when life calls for it.

More articles from Criselda Yabes

No comments:

Post a Comment